In this special report, Housing Is A Human Right advocacy journalist Patrick Range McDonald reveals the financial ties and behind-the-scenes connections between Big Tech, California YIMBY, and State Sen. Scott Wiener. Largely unknown until now, this investigation shows that these powerful forces have banded together to push a troubling, pro-gentrification housing agenda in California. That includes SB 50 — the land-use deregulation bill that’s opposed by leading housing justice organizations. We also recommend reading our updated article on the corporate interests that fund California YIMBY.

Part I: Big Tech is the Mothership

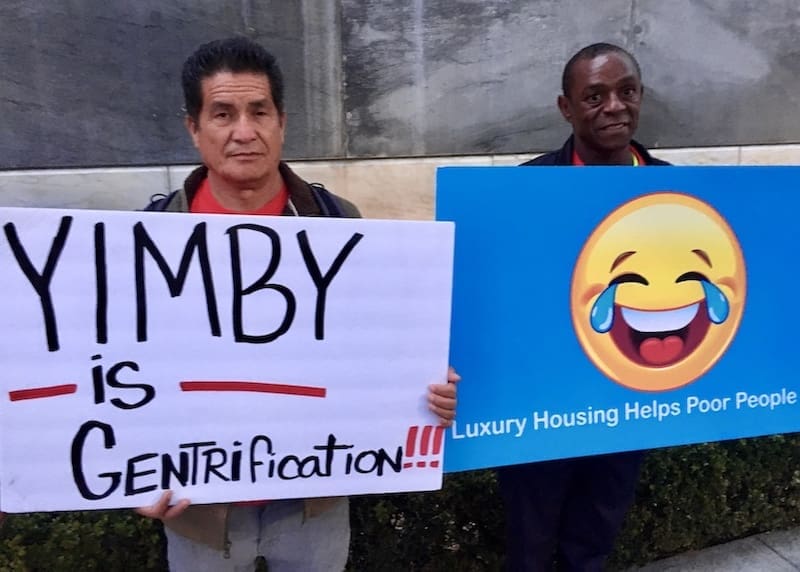

On the steps outside San Francisco City Hall, on a blue-sky Tuesday in April 2018, a group of grassroots activists and residents — many of whom were people of color — held a press conference to denounce SB 827, a statewide, land-use deregulation bill. California State Sen. Scott Wiener introduced the controversial legislation, and a fledgling organization called California YIMBY helped craft it. The residents and activists believed SB 827 would be catastrophic, adding jet fuel to a gentrification crisis that was already decimating San Francisco’s working-class communities, especially those of color.

“We’ll keep fighting,” Charles Dupigny, the African American co-director of Affordable Divis, told the crowd. “We’ll keep moving forward. We plan to keep fighting this bill, like many times in the past in San Francisco.”

But as Dupigny talked, a young, mostly white group of self-identified “YIMBYs” aggressively inserted themselves into the press conference, refusing to listen. In fact, they were trying to silence Dupigny, yelling at him, “Read the bill! Read the bill! Read the bill!” Their brashness wasn’t surprising.

In California, YIMBYs (YIMBY stands for “Yes In My Back Yard,” a clever twist on NIMBY or “Not In My Back Yard”) have made headlines by forcefully advocating for widespread land-use deregulation that, in their eyes, would solve the state’s ongoing housing affordability crisis.

The YIMBY agenda plays out this way: deregulate as much as possible, an apartment construction boom will follow, and sky-high rents will stabilize and drop since more units have come onto the market. It’s the old, possibly outdated, supply-and-demand argument.

Housing justice activists rightly counter that developers build almost exclusively luxury housing, which not only does nothing to directly help middle- and working-class Californians — who are hit hardest by the housing affordability crisis — but also worsens the problem.

Underlining that point, Zillow, the real estate site, found that in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and other major cities, “very high demand at the low end of the market is being met with more supply at the high end, an imbalance that will only contribute to growing affordability concerns for all renters.”

Zillow Chief Economist Dr. Svenja Gudell added: “Apartment construction at the low end needs to start ramping up, and soon, in order to see real improvement.”

YIMBYs don’t want to hear that. In fact, they routinely show a visceral dislike for anyone who challenges their supply-side, deregulation belief system — whether it’s using Twitter to pile on critics or immediately shouting them down in public. Now, on the steps of San Francisco City Hall, that hostility was on frightful display.

After Dupigny spoke, the YIMBYs continued their menacing counter-protest. Things got so out of hand that one resident, a 77-year-old Asian woman, fainted — and was shuttled to a hospital. Sonja Trauss, a contentious, outspoken leader among the YIMBYs, was so fierce that sheriff’s deputies moved her away from the crowd.

“Our members were intimidated by YIMBY,” Wing Hoo Leung, president of the Chinatown-based Community Tenants Association, told the San Francisco Examiner. “They felt threatened.”

Lueng added, “I think the YIMBY have no heart.”

The showdown at San Francisco City Hall was not an aberration, but another nasty example of YIMBYs’ hard-core militancy.

“It’s been absolutely ugly,” Bay Area activist Shanti Singh told Shelterforce in 2019, describing her interactions with YIMBYs. “A really nasty three years.”

Maria Zamudio, another Bay Area activist, told In These Times, “They’re like, ‘Just build housing, you stupid brown people! I moved here last week, and I need a place to live!’”

Fernando Marti, co-director of the San Francisco-based Council of Community Housing Organizations, wrote in a Shelterforce column: “But according to the YIMBY leaders, now we equity advocates are the problem too, little different from the NIMBYs, rabid progressives who are too naïve or ideological to understand how the market really works. In this story line, in the name of fighting evictions and displacement, we progressives, we communities of color, we poor people and immigrants, we working-class queers stupidly don’t realize that luxury development now will eventually become the affordable housing of the future!”

Despite this appalling track record, the YIMBYs are, more times than not, warmly embraced by the mainstream media. Only months after the fracas in San Francisco, for example, Bloomberg Opinion columnist and economics professor Tyler Cowen gushed that the “YIMBY movement is definitely on to something” and Bill Boyarsky, the former city editor of the Los Angeles Times, wrote a glowing op-ed in support of YIMBY. Politicians, such as State Sen. Scott Wiener, a moderate Democrat who represents San Francisco, and San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer, also proudly align themselves with YIMBYs.

On the face of it, one may think that developers, who despise land-use regulations, have been the monied force behind the ascendency of YIMBYism. But, in California, that’s not really the case, although a powerful industry, with global clout, is making things happen behind the scenes. That minted behemoth? Big Tech.

Over the past four years, Big Tech has quietly built a power base to push through land-use and housing policies that benefit the tech industry above anyone else. SB 827, which was stopped in 2018, was legislation that Big Tech desperately wanted to pass. SB 50, the controversial follow up to SB 827 that’s still alive in the state legislature, is another Big Tech-backed bill.

The tech industry’s key agents are California YIMBY, the statewide lobbying group founded and funded by tech executives, and State Sen. Scott Wiener, who, since 2015, has socked away a staggering $554,235 in campaign cash from Big Tech, including sizable contributions from Facebook, Google, and Amazon. California YIMBY and Wiener worked closely for SB 827, and they’ve teamed up again for SB 50. California YIMBY and Wiener are inextricably linked — and Big Tech is the mothership.

In a revealing 2017 article, Pantheon CEO Zack Rosen, who co-founded California YIMBY, explained Big Tech’s jump into land-use and housing policy. He told The Information, a news site for tech insiders, that a “combination of over-regulation by the state and the tech industry’s success has created the [housing] problem. I feel there’s a real onus on us to lead.”

But with millions of middle- and working-class Californians struggling to pay exorbitant rents, Big Tech’s need to lead was hardly altruistic.

What pushed tech executives into action, Rosen candidly told The Information, was that the housing affordability crisis had become an “existential threat” to the growth of the tech industry.

In other words, California YIMBY, fully staffed with organizing directors, assistants, a lobbyist, and policy wonks, and State Sen. Scott Wiener, the most aggressive California legislator of YIMBY policies, are carrying out an orchestrated defense, and expansion, of Big Tech’s gigantic profits.

Part II: Big Tech Bets on Scott Wiener

Nearly nine years ago, Big Tech started placing bets on Scott Wiener, rated the “most moderate, or right leaning” politician in San Francisco by the San Francisco Public Press and UC Davis. Wiener graduated from elite schools — Duke University and Harvard Law School — and worked as an attorney for an international law firm and then at the San Francisco City Attorney’s Office. He has a privileged pedigree that’s attractive to Big Tech executives, many of whom come from similar backgrounds.

Between 2010 and 2014, when Wiener first ran for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and then campaigned for re-election, he raked in small contributions, worth a few hundred dollars each, from employees of Google, Cisco Systems, Facebook, Yahoo, and Salesforce, among others. At the same time, Wiener was also pocketing major campaign cash from the real estate industry. Wiener then decided to run for the California State Senate in 2016. Ever since then, Big Tech has poured money into his campaign coffers.

According to state filings, Yelp, Google, Facebook, Amazon, Tesla, the Technet Political Action Committee, Lyft, Paypal, Oracle, Yelp, Hewlett Packard, Uber, Intuit, Salesforce, and hundreds of tech executives, employees, and tech investors, including prominent angel investor Ron Conway, have shelled out 564 contributions to Scott Wiener’s 2016 and 2020 state senate campaigns, totaling a whopping $554,235. (So far, Big Real Estate has delivered $803,113 to Wiener since 2015.)

(See Scott Wiener’s Big Tech campaign contributions for 2016 and 2020.)

Wiener banked $4,200 campaign checks from Facebook, Salesforce, tech investor Laura Lauder, Dropbox vice president Aditya Agarwal, Facebook vice president Sean Ryan, and Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff. He also received $4,200 checks from Airbnb chief executive officer Brian Chesky and tech investor Stewart Alsop and a $4,400 check from the Technet Political Action Committee, a national lobbying group for the tech industry. Dozens of employees at Facebook, Google, Airbnb, and Salesforce sent campaign cash to Wiener.

The moderate San Francisco politician didn’t disappoint Big Tech.

As Wiener ran for the state senate, he opposed the 2016 “Tech Tax.” The proposed San Francisco ballot measure would have levied a payroll tax on tech companies, raising tens of millions each year to build affordable housing and fund homeless services. Housing justice activists supported the initiative as a way to urgently address San Francisco’s homeless emergency. But it didn’t get enough support from the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, including Wiener, and failed to land on the city ballot. The Tech Tax, which Big Tech vigorously opposed, went nowhere.

That same year, Wiener again sided with Big Tech, and went against housing justice activists, by backing Proposition Q. The San Francisco ballot measure allowed the city to more easily clear homeless encampments, essentially criminalizing homelessness. While Big Tech didn’t want to be taxed to help the homeless, the industry wholeheartedly supported and funded Prop Q to sweep unhoused individuals off the streets. Voters approved the initiative.

With Wiener’s stances on the Tech Tax and Prop Q, Big Tech continued writing generous checks for Wiener’s 2016 state senate campaign — and he needed it. Although Big Tech and Big Real Estate were shelling out tremendous amounts of cash to Wiener, he found himself in a tight race against San Francisco Supervisor Jane Kim, a lesser-funded opponent who had earned an endorsement from U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. It looked as if Kim, a progressive Democrat, could pull off an upset.

But as is too often the case, the money won out — Wiener, the definition of a “Corporate Democrat,” was victorious by the minuscule margin of 8,146 votes. He had Big Tech, and Big Real Estate, to thank for his sudden rise in power and influence — he could now push far-reaching legislation that would impact the length and breadth of California. Wiener’s win, of course, was also a victory for the tech and real estate industries — they now had a reliable friend, who owed them big favors, in the state senate.

Wiener and Big Real Estate have always shared the same agenda: deregulate the housing market and construct as much luxury housing as possible. It’s a surefire way for the real estate industry to generate billions in revenue — developers can build whatever they want, wherever they want.

Wiener and the real estate industry try to camouflage that profit motive by insisting that deregulation and massive construction are the perfect antidotes for California’s housing affordability crisis. It’s simply an issue of supply and demand, they say. YIMBYs constantly broadcast this notion, too, with the mainstream media often providing a 50,000-watt megaphone.

Undergirding that is a core, perhaps insincere, principle held by Wiener, Big Real Estate, and YIMBYs that a “free market” can work miracles, but only if regulations are slashed and discarded.

Yet there’s a reason Big Real Estate executives — and Big Tech and YIMBYs, for that matter — hire scores of lobbyists to work their high-priced magic inside the backrooms of state and local politicians: through legislation, they’re gaming the so-called “free market” to work for them. The 1995 Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act and 1985 Ellis Act, California laws that dramatically rigged the market in favor of the real estate industry and remain on the books today, are just two onerous examples.

Wiener and Big Real Estate’s agenda is known as “trickle-down” housing, which many say fuels gentrification and higher rents in middle- and working-class communities where luxury apartment complexes are built.

“Trickle-down housing contributed to our affordability crisis,” wrote San Francisco Supervisor Gordon Mar in a newspaper op-ed, “and trickle-down housing won’t solve it.”

Even Richard Florida, an urban planning guru for politicians like Wiener, wrote that “the markets — and neighborhoods — for luxury and affordable housing are very different, and it is unlikely that any increases in high-end supply would trickle down to less advantaged groups.”

Activists also argue that the state’s housing affordability crisis is impacting, first and foremost, middle- and working-class residents, especially those of color.

“Throughout the state,” a 2019 report by the California Budget & Policy Center stated, “many of the individuals affected by unaffordable housing costs are people of color. Among all Californians living in households paying more than 30 percent of income toward housing costs in 2017, more than two-thirds were people of color, and about 45 percent were Latinx.”

Those renters can’t afford new luxury housing — and they’re struggling, right now, to pay excessive rents and keep roofs over their heads. Trickle-down housing, activists say, does nothing to directly, and urgently, build much-needed affordable housing for an ongoing housing affordability crisis.

What’s more, there’s no guarantee that luxury housing will become affordable years, even decades, from now. According to the California Legislative Analyst’s Office, it will take some 25 years for that possibility.

In addition, regulations, or local zoning ordinances, can protect middle- and working-class neighborhoods from runaway gentrification and luxury-housing development, and force developers to include affordable housing in their market-rate projects. Regulations keep developer greed in check — and allow residents to have a say in what kind of development goes into their communities.

Unsurprisingly, Wiener, a kind of modern-day Robert Moses who wants to build, build, build no matter the consequences to vulnerable communities, and Big Real Estate wave off those points. The same goes for a group of well-educated, young professionals who proudly describe themselves as YIMBYs. The YIMBYs adore new luxury housing, and, like Wiener and Big Real Estate, don’t worry about the negative impacts on middle- and working-class neighborhoods.

“The YIMBY movement has a white privilege problem,” Anya Lawler, a policy advocate with the Western Center on Law & Poverty, told the Los Angeles Times. “I don’t think they recognize it. They don’t understand poverty. They don’t understand what that’s like, who our clients really are and what their lived experience is.”

A few years ago, YIMBYs formed groups in Northern and Southern California, supporting luxury-housing developers and promoting the YIMBY agenda. But they weren’t always organized, they weren’t huge in numbers, and they constantly butted heads with housing justice activists. YIMBYs, however, were loud and forceful — they weren’t afraid to mix things up, for example, at a local government meeting or on the steps of San Francisco City Hall. Big Tech took notice.

Part III: Big Tech Sets Up California YIMBY

In the Bay Area, over the past several years, things were becoming increasingly uncomfortable for Big Tech: a rock thrown through the window of a Google bus; protesters taking to the streets to blast the tech industry for fueling sky-high rents; the tech industry barely avoiding the proposed “Tech Tax” in San Francisco. A Big Tech backlash was ramping up.

The primary beef leveled at the tech industry was that it wasn’t addressing its impact on middle- and working-class communities. As Big Tech expanded wildly in Silicon Valley and the Bay Area, the growing number of well-paid techies needed somewhere to live. That often meant they moved into “up-and-coming” neighborhoods that were affordable, but, with the influx of Big Tech employees, turned into high-rent districts, fueling gentrification. The techies could afford the rising rents. Middle- and working-class residents could not.

For a report on gentrification in San Francisco, Causa Justa :: Just Cause, a housing justice organization, wrote: “Both the Tech and the Real Estate Industries have to take responsibility for the affordability crisis in San Francisco. Blaming Real Estate is an easy out for Tech companies that claim to be ‘innovating for social good,’ but ignore the impact their boardrooms of innovation have on surrounding communities. Meanwhile, Real Estate happily lets Tech workers take the blame for their reckless profiteering, hiding behind the myth that the housing market is some kind of force of nature, instead of a real time series of power relationships that human beings have responsibility for. In the background of each wave of gentrification, each massive increase in rents, each conversion of a rent-controlled apartment into a luxury condominium is an incredibly powerful finance industry that shapes not just San Francisco, but California as a whole.”

Indeed. Similar issues were taking place in Los Angeles’ “Silicon Beach” on the Westside, especially in Venice, where the once diverse, working-class beach community turned into one of the most gentrified neighborhoods in L.A.

In an L.A. Taco article, resident Mike Bravo described Snapchat’s impact on Venice as “a hyper example of the gluttonous gentrification that’s been going on in the neighborhood.”

Faced with growing ill will and bad public relations, Big Tech understood it needed to act.

Long embedded in its culture, Big Tech has an enormous aversion to regulation — at least the kind of regulation that doesn’t benefit the industry. Tech executives have also shown a reluctance, perhaps an unwillingness, to consider the long-term, street-level impacts of their products — think of the weaponized use of social media by politicians, the rising rents and loss of long-term housing stock because of Airbnb, the countless deaths of small businesses, such as bookstores and record stores, because of Amazon, and the invasion of privacy thanks to data mining by Google. YIMBY’s culture — big on deregulation and purposefully ignoring the street-level problems brought up by housing justice activists — matched perfectly.

Unalarmed by YIMBYs’ constant clashes with the housing justice movement, Pantheon CEO Zack Rosen reached out (through Twitter, appropriately enough) to Bay Area YIMBY ringleader Brian Hanlon. Rosen needed someone to helm California YIMBY, a new organization he wanted to start up.

Rosen, who studied at the University of Illinois and whose interests include bicycling, camping, and dinner parties, and Microsoft executive Nat Friedman, who graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and whose tech company, Xamarin, was bought by Microsoft for somewhere between $400 and $500 million, wanted California YIMBY to lobby state legislators and draft Big Tech-backed housing bills. The tech industry also needed ground troops to counter the inevitable ire of housing justice groups and community activists.

For Rosen and Friedman, Brian Hanlon was a sensible choice. He had co-founded a YIMBY-type group called California Renters Legal Advocacy and Education Fund, which sued cities that may have violated state housing law. In his mid-thirties, outspoken, tall, and shaggy-haired, Hanlon, who aspires to someday work at a natural wine bar, was a visible YIMBY presence in the Bay Area and hyper-educated, receiving master’s degrees from George Mason University and Northwestern University. Like Wiener, Hanlon had the kind of top-drawer background that matched well with his Big Tech suitors.

Hanlon was inserted as the president and chief executive officer of California YIMBY. Rosen took the role of secretary treasurer. Friedman became chairman. Immediately, other tech executives sent checks to California YIMBY, including Yelp CEO Jeremy Stoppelman, tech investor Jared Friedman, and Stripe executive Cristina Cordova.

But since California YIMBY is a non-profit, it doesn’t have to disclose the names of donors, making it difficult to know who else has contributed. And the organization seems intent on staying non-transparent — Hanlon tries to keep mum on exactly who is giving what.

But during an interview with The Real Deal, Hanlon let it slip that Big Tech was, indeed, delivering cash to California YIMBY — and that he was also eyeing Big Real Estate for checks.

“I am certainly willing to accept money from developers,” he told the real estate news site, “it’s just that I’ve gotten a much better reception from tech leaders than from real estate people.”

Within the first year, California YIMBY had reportedly raised $500,000.

As California YIMBY emerged as a statewide lobbyist for Big Tech’s deregulation policies, housing justice activists were justifiably on guard.

Peter Cohen, co-director of the Council of Community Housing Organizations, told The Information: “The losers in this deregulation agenda will be the working class and lower-income communities of color in these hot markets, which are the major cities in California. The tech industry jumping into the housing situation is a self-interested political calculation.”

Then, in 2018, California YIMBY came into a windfall. Big Tech executives Patrick and John Collison, co-founders of Stripe, went all in, handing over a $1-million check. The eye-popping contribution became a national headline in the New York Times.

With tech executives Rosen and Friedman continuing to guide things, California YIMBY put that largesse to good use. The organization employed a registered lobbyist in Sacramento, an organizing director and six regional organizing directors who work throughout California, a digital director, a digital and data associate, a finance and operations director, a chief operating officer, a Southern California policy director, an executive assistant, a director of organizing product management, a director of communications, and a policy assistant. California YIMBY also plans to hire a regional organizing director for the Central Valley and a director of individual and corporate giving for more fundraising.

California YIMBY’s official, self-described “tripartite” strategy is Policy Development (“formulate policy & draft legislation”), Inside Game (“Work with elected officials & build an interest group coalition”), and Grassroots Pressure (“Empower existing YIMBY groups & organize a new statewide movement”). To that end, California YIMBY’s regional organizing directors work with 10 local YIMBY groups in the Bay Area, three in the Los Angeles area, six in Orange County, and two in San Diego. There are also YIMBY groups in Sacramento, Riverside County, and Central California.

A key part of California YIMBY’s “inside game” is to lobby state legislators. According to state filings, the organization spent $96,868 on lobbying for numerous state bills during the first quarter of the 2019-2020 legislative session in Sacramento. It spent $135,936.54 during the second quarter and $89,517 during the third quarter. That’s a substantial sum of $322,321.54. California YIMBY hired lobbying firms Lighthouse Public Affairs and Dewey Square Group. It also employed an in-house lobbyist, Louis Mirante.

Another important tool for the organization’s inside game is California YIMBY Victory Fund — a political action committee that doles out campaign cash to mostly state politicians. The PAC, according to state filings, has been funded by Nat Friedman and Patrick Collison ($10,000 contributions each); Jared Friedman ($20,000); and Stripe (a hefty $100,000). Along with other tech insiders, Arista Networks co-founder Kenneth Duda also threw in two checks of $100,000 each.

Since 2018, California YIMBY Victory Fund has delivered campaign checks to California State Treasurer Fiona Ma ($500), California State Senate President pro Tempore Toni Atkins ($2,000), State Assemblymember Tyler Diep ($2,000), State Assemblymember Buffy Wicks ($2,000 and $35,000 for a campaign committee that supported Wicks), State Senator Josh Newman ($4,400 and $100,000 for a failed effort to fend off a successful recall campaign), State Senator Nancy Skinner ($4,400), San Francisco Mayor London Breed ($500), State Sen. Anna Caballero ($4,400 and $40,000 for a campaign committee that supported Caballero), and many others.

With the lobbying and contributions, politicians understand it’s not just California YIMBY meeting with them and handing out money. Things go deeper than that. It’s Big Tech, who’s financing California YIMBY’s lobbying efforts and PAC, that the politicians are interacting with — a powerful industry that many elected leaders want to be connected to, if only to tap into Big Tech’s campaign cash.

Big Tech, through California YIMBY, was covering all its bases, funding the campaigns of state policy makers and a statewide lobbying group — California YIMBY was hardly borne out of grassroots power. Tech executives also didn’t forget to keep throwing money at Scott Wiener, the state senator expected to ram through Big Tech’s housing agenda in Sacramento.

Since 2016, according to state filings, California YIMBY contributors Patrick and John Collison have personally sent a total of $26,600 in campaign cash to Wiener. California YIMBY co-founder Nat Friedman has shelled $8,800. California YIMBY contributors Jared Friedman delivered $2,750 and Jeremy Stoppelman handed over $7,700. Other California YIMBY contributors in Big Tech may have forked over campaign contributions to Wiener, but the public doesn’t know because California YIMBY refuses to be transparent about its donors.

(See Scott Wiener’s Big Tech campaign contributions for 2016 and 2020.)

With those king-sized checks in his campaign coffers, State Sen. Scott Wiener understood the expectations of Big Tech. The same way he knew, as a candidate, that he had to oppose the Tech Tax and support Proposition Q. Wiener needed to move into action. California YIMBY would be close by his side.

Part IV: Big Tech Pushes Trickle-Down Housing

On Wednesday, January 3, 2018, only days after a British newspaper reported about California’s devastating housing affordability crisis to the world, Scott Wiener introduced a land-use deregulation bill called SB 827. At the core of the legislation was the trickle-down, luxury-housing agenda championed by Big Real Estate, Big Tech, and California YIMBY. Wiener and crew, in other words, wanted to build luxury housing for a housing affordability crisis. Housing justice activists instantly smelled a rat, but the national media largely fawned over the bill. Big Tech’s fingerprints were all over the legislation: California YIMBY CEO Brian Hanlon helped draft SB 827.

Only weeks later, on California YIMBY letterhead, Nat Friedman, Zack Rosen, Jeremy Stoppelman, Patrick Collison, Jared Friedman, and more than 120 Big Tech executives sent a letter to Wiener, pledging their support for SB 827. The leaders, many of them millionaires and a few billionaires, mentioned nothing about gentrification and homelessness, quickly mentioned displacement and high rents, and mostly focused on themselves.

“We hope to grow our businesses in California,” wrote the Big Tech executives, which included, among others, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, Lyft CEO Logan Green, and tech investor Ron Conway, “but it’s difficult to recruit and retain employees when they could accept jobs in other states and pay a fraction of California’s housing costs. Already, many California-based technology firms have accelerated hiring in other states because housing costs are too high. SB 827 will provide housing opportunities for many Californians while permitting our firms to increase good jobs and improving the fiscal position of the state budget.”

In one paragraph, Big Tech executives revealed their profit-driven motive behind its housing agenda, with California YIMBY and Wiener leading the push.

While housing justice activists and working-class residents in California were fighting predatory landlords, advocating for much-needed affordable housing, and dealing with the crushing ripple-effects of gentrification-inducing luxury housing, the Big Tech executives used up a solid paragraph in their short letter to explain how their well-paid employees were facing “punishingly long commutes.” From the start of the SB 827 battle, there was a disconnect between Big Tech (and California YIMBY) and the housing justice movement.

In a March 2018 article, housing activist Jacob Woocher, sounding a belief held by many activists, wrote that SB 827 is “a lubricant for gentrification that places the burden of luxury development and its accompanying displacement squarely on communities of color filled with renters.”

The Los Angeles-based Black Community, Clergy and Labor Alliance wrote their own letter to Wiener.

“Private interests and practices intended to reclaim urban space to profit a global investor class and real estate speculators are direct threats to our right to the homes and communities that we built in the face of their oppression,” the group stated.

“Unfortunately, public policies like SB 827 are not a defense, but rather an aid for these oppressive and discriminatory policies and interests. And there is nothing courageous, new or innovative about advancing land grabs and economic exploitation.”

An intense clash broke out between Big Tech’s California YIMBY and the housing justice movement, which culminated with YIMBYs shouting down people of color at the April press conference on the steps of San Francisco City Hall. That disturbing counter-protest did not help. On April 17, 2018, a California State Senate committee killed the bill.

“Right now, the statistics show that predominantly the demand is for affordable housing and for homeless and [Wiener’s] proposal didn’t provide for that,” said California State Senator Jim Beall.

A few months later, California YIMBY and Wiener failed to endorse Proposition 10, the 2018 statewide ballot measure that sought to allow communities to expand rent control and urgently address the housing affordability crisis. Big Tech also sat on the sidelines, failing to send campaign contributions to the Yes on Prop 10 effort — tech executives didn’t even write a letter of support.

In stark contrast, more than 525 social justice and housing justice organizations, unions, and political leaders, including U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders and labor union icon Dolores Huerta, endorsed Prop 10. The Nation deemed it one of the “more vital” progressive battles in the country.

California YIMBY, Wiener, and Big Tech didn’t care.

Big Real Estate, a major campaign contributor to Weiner, ended up spending $77.3 million to successfully stop Prop 10 with deceptive, and constant, TV commercials. California YIMBY and Wiener’s refusal to endorse, and Big Tech’s indifference, was one more reason the housing justice movement couldn’t trust them.

On top of that, Big Tech and Wiener strongly opposed a 2018 San Francisco ballot measure, Proposition C, that sought to tax the city’s largest businesses to generate more money for homeless services. In fact, instead of contributing big bucks to the Yes on 10 campaign, Big Tech was busy financing a No on Prop C committee: Twitter’s Jack Dorsey shelled out $75,000, Stripe (a major contributor to California YIMBY) gave $419,999, and Lyft spent $100,000. This time, voters sided with housing justice and homeless activists, and approved the initiative.

Then, only weeks after the defeat of Prop 10, California YIMBY and Wiener rolled out the successor to SB 827, known as SB 50. Wiener admitted it was essentially the same. It was like adding salt to the wounds of many housing justice activists.

“We remain skeptical of Senator Weiner’s intent with SB 50,” said René Christian Moya, director of Housing Is A Human Right, the housing advocacy division of AIDS Healthcare Foundation, “especially since he’s taken more than $150,000 in campaign contributions from major real estate interests and Prop 10 opponents. Money talks.”

Big Tech executives kept a lower profile for the SB 50 fight, but their lobbying organization, California YIMBY, was still leading the charge, utilizing its “inside game” to win support from elected officials. That included several politicians who hauled in campaign cash from the California YIMBY Victory Fund, such as State Sen. Toni Atkins, State Sen. Nancy Skinner, Assemblymember Tyler Diep, Assemblymember Buffy Wicks, State Sen. Anna Caballero, and San Francisco Mayor London Breed.

Against bad odds, housing justice activists were still successful in stalling SB 50, although Wiener and California YIMBY have brought it back again this month. Another bruising battle is expected. State Sen. Toni Atkins, who received a sizable campaign check from the California YIMBY Victory Fund, said she will take a more hands-on approach with the bill, but already the San Francisco Board of Supervisors has opposed it. Big Tech, through the California YIMBY Victory Fund, also delivered a whopping check of $4,700 to Wiener on December 6, 2019.

Perhaps learning a lesson or two, California YIMBY is now co-opting messaging from the housing justice movement, dubiously claiming that SB 50 “includes strong protections for renters.” Housing activists aren’t buying it.

“SB 50 proclaims to protect rent-controlled units,” Jackie Fielder, a San Francisco community organizer who’s currently running against Wiener, and Deepa Varma, executive director of the San Francisco Tenants Union, explained in a recent San Francisco Examiner op-ed, “yet barely over a dozen California cities have any rent control, and what they do have is severely limited by the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act. Furthermore, the ‘anti-demolition’ clause, which is supposed to protect tenant housing, is actually an invitation for real estate speculators to vacate currently rented housing and hold it off the market for some years in anticipation of windfall profits later. As we are seeing with the Black-women-led Moms 4 Housing collective in Oakland, speculators will sit on vacancies while thousands go unhoused. SB 50’s vacancy protection is limited and also nearly impossible to effectively enforce in the majority of California cities that lack demolition protections and rental registries.”

For many activists, the stained memory of Big Tech’s ground troops clashing with activists in San Francisco and sending an elderly woman to the hospital is a hard one to forget. It’s the kind of roughshod treatment too many working-class residents in California have suffered at the hands of deep-pocketed industries and pro-corporate politicians who push through legislation that puts Big Business’ profits over people. The rise of Big Tech’s California YIMBY is one more chapter in that long, ugly history.

About the author: This investigative report was researched and written by Patrick Range McDonald, the advocacy journalist for Housing Is A Human Right.

Top photo by Leslie Dreyer/Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco